Three Indian Air Force fighter pilots held as Prisoners of War in a jail in Rawalipindi made a heroic escape. They reached as far as the Pak-Afghan border in Pakistan’s Wild West -- within sniffing distance of freedom -- only to realise that they had finally met their match. Or so it seemed.

The three escapees were never feted for their audacious attempt 41 years ago and truly deserve official recognition. Why not honour them at least now, says MP Anil Kumar in the second part of his brilliant account of that Great Escape.

Welcome to Khyber' -- an arch greeted at Jamrud, but, ironically, the subtext cautioned the visitors into looking over their shoulder! The barren terrain and the grim tribesmen armed to the teeth lent an air of hostility all around. The cold gaze of the locals rubbed the feeling of being an interloper in. What a welcome to Khyber!

Had better get out of this place pronto. A few steps into their stride, a passer-by warned sternly of waylayers. Minutes later, a small boy grinned, shaped his hand into a pistol and pulled the imaginary trigger. They indulged the kid, mimicked cowboy draws, played peek-a-boo. He asked who they were. “Pakistani.” “Pakistani nahin, Hindustani hain,” he dropped a bombshell, beamed and chugged away. The tremble it triggered registered on the Richter scale. Footing it to Landi Kotal was perilous.

The trio hopped on to a bus. The panoptic view of the harsh environment from the rooftop impelled them into appraisal. Their original plan was to hide daylong and find their way at night. They would not have made it; if the Pathan did not get them, his bloodhound would. The benevolent nudge of Providence?

As they debussed at Landi Kotal, Parulkar glanced at the watch: 0930 hrs. A tad over nine hours since they embarked on the venture. Torkham was mere five miles away. Since they did not know which of the two routes led to Landi Khana, they strolled to a tea stall, chatted up like tourists, sipped the piping hot beverage and tossed the query.

Bewilderment suffused the faces of bystanders; they shook their heads as if they were asked to spell and pronounce feuilleton! Strangely, Landi Khana was known to none, but relief and directions manifested eventually: Four miles, no bus, only taxi, fare 30 rupees. Thirty rupees for four miles? Nope. Shank’s mare.

The townsmen sported a particular type of skullcap. As this accessory might dilute their conspicuousness, Parulkar purchased two, for Grewal and himself (no-no for ‘Anglo’ Harold Jacob). Meanwhile a hailer offered taxi-fare of 25 rupees. Not a bad bargain. As they budged, a bespectacled, bearded, auburn-haired gent accosted them, rapid-fired who, what, where, why, when. Of course, they were two PAF airmen and a chum on tour…

As a small crowd began congregating, the unimpressed man quizzed about Landi Khana; Grewal replied nonchalantly that the place was there on all maps. Why the fuss? Why? Why? Why indeed?

The British built Landi Khana (near Torkham) as the railhead of Khyber Pass Railway but they closed the station in December 1932! Which was why the townspeople were oblivious of the rail terminus. They fell into the man’s trap. The heroes had finally met their match.

The busybody had more ammunition: he accused them to be East Bengalis scooting to Afghanistan. “Have you seen Bengalis ever? Do we look like Bengalis?” the troika shot back, then guffawed aloud for effect in a desperate effort to reclaim fast-losing ground. The audience did not find it funny.

The man, the tehsildar’s clerk, was on Sunday-morning-constitutional. ‘Landi Khana’ raised an internal alarm, and he kept them in his sights since. Apparently, fleeing Bengalis bought the Peshawari topee here, not from Peshawar itself. The topee, to him, was the clincher. At first, he doubted them to be outlanders, but revised his suspicion afterwards to Bengalis.

Whatever, the topee sealed their fate. He marched them under armed escort to the tehsildar.

The clever clerk opened a chapter of misfortunes. The tehsildar quizzed them, remained impervious to the cock and bull story, and bade the gunmen to lock them up in jail. Their goose was seasoned and cooked. Parulkar’s nous envisioned a fate worse than the firing squad. Only a masterstroke could save their neck, and he pulled one out of the topee: he requested the tehsildar to make a phone call, which was conceded to grudgingly.

The ADC to the Air Chief came on the line. He modulated English to perplex the Pashto-tongued lot, told Usman about being held captive by the tehsildar and entreated him to send his men. Usman told the tehsildar they were indeed Pakistani airmen, to throw them behind bars but not to harm physically.

The ADC to the Air Chief came on the line. He modulated English to perplex the Pashto-tongued lot, told Usman about being held captive by the tehsildar and entreated him to send his men. Usman told the tehsildar they were indeed Pakistani airmen, to throw them behind bars but not to harm physically.

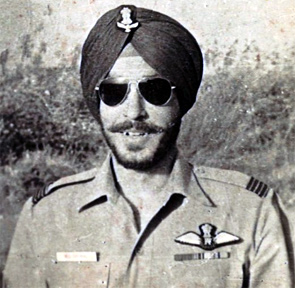

[Left: MS Grewal was conferred a Vir Chakra but that was for his gallant action prior to the ill-starred sortie]

The guardroom telephone came alive at about 11 o’clock and rang the knell of the mounting suspense. Soon, [back in the Rawalpindi jail] V S Chati heard approaching footfalls, two air force policemen barged in, turned the furniture inside out, kicked the dummies, cast dirty look, stormed out and confabulated, within earshot, with their colleagues.

Why not dump the roomie into the ‘escape hole’, shoot him to show they were vigilant? Chati perspired cold sweat. Since the air chief was already in the loop, a dead body would in no way extenuate the dereliction. Reason prevailed; Chati lived to tell the tale.

The jail was far-off. The cop scoured their personal effects and impounded it including the POW identity cards. As they contemplated the worst in the reeky coop, the tehsildar materialised flanked by a bunch of brawny flunkeys. He, nostrils flared, demanded details afresh. The cop had sneaked and passed on the identity cards; they had to reveal their real selves. That he was outwitted by ‘Hindu POWs’ boiled his blood; he, in a paroxysm of pique, let fly an invectives-laden outburst. Hogtied, he paraded his prize-catch through the town, past his office as well.

The lynch law ruled this lawless expanse. They fretted like an antelope about to be pounced on by a pride of lions. Would he consign them to a bloodthirsty mob?

He handed them over to Mr Burki, the political agent of Northwest Frontier Province (a vestige of British Raj). He and his posse of toughies were chagrined to disbelief when the suave political agent motioned to unfetter. Usman had dialled and urged him to intervene as a personal favour. What a lifeline the call to Usman turned out to be.

They were served a toothsome spread. As they began savouring the five-star hospitality, at about 4 o’clock, a squad of PAF police stomped in. Before the three were manacled, blindfolded and hustled to the PSF in Peshawar, Burki, to tease them, pointed at a close-by range and disclosed the other side as Afghanistan! Ah, freedom was within sniffing distance! Heartbreaking.

Grewal and Harish were detained in individual cells. For the want of an additional cell, an office was hastily furbished into a makeshift clink for Parulkar. His attention gravitated to the brazier’s chimney and vent; he rubbed his hands. If he could enlarge the void, if he could thrust his head out, well.

The irrepressible Parulkar could not resist the temptation to essay another escape. He hoisted a chair on the office-table, clambered it and pounded the loose cement about the vent with a shaft uprooted from the fireplace. Before long, a sergeant discovered the enterprise, swapped coop with Grewal and trussed up the culprit to the door.

Deprived of nightlong sleep, a red-hot Parulkar protested vehemently in the morning, cited chapter and verse from the Geneva Convention and reminded who the victor was. The PSF fell in line.

On his return, Wahid-ud-din let off steam on the seven [other IAF POWs in the Rawalpindi jail from where the trio had escaped], initiated steps to pack them off to the fortress-like jail in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad). There, the seven were corralled with the 500-odd army POWs.

The three heroes were turned over to the Rawalpindi camp, where the camp commandant, after a summary trial, sentenced them to 30 days’ solitary confinement. Few days later, they too were transferred to Lyallpur, where the verdict was commuted.

The three heroes were turned over to the Rawalpindi camp, where the camp commandant, after a summary trial, sentenced them to 30 days’ solitary confinement. Few days later, they too were transferred to Lyallpur, where the verdict was commuted.

[Left: Harish Sinhji retired as group captain in 1993]

End-November, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, then premier of Pakistan, addressed the POWs and declared their repatriation. The returnees were bestowed a hero’s welcome at the Wagah border on December 1, 1972. A grand reception awaited the ten IAF officers at the air force unit in Amritsar. They were flown down to Delhi in the evening where they were toasted and reunited with their kith and kin. Could any homecoming be sweeter?

Epilogue

* What a damn good fist they made of the bid to escape. A smidgen more of the rub of the green, the exploit could have had a storybook climax, and enshrined the feat. Could the escapees have done anything differently? On the Jamrud road, maybe (big maybe) they could have hired a cab away from the prying public, sweet-talked and inveigled the driver into taking offbeat tracks till Torkham, onwards to Kabul, and requested the Indian embassy to reward the driver for his pains.

The dozen POWs were fighter pilots who had to eject over Pakistan, and some sustained minor to major injuries. While only the three were involved in the escape, every officer, including the unnamed ones in this narration, put their shoulder to the wheel. For example: B A Coelho drew out the compass rose; J L Bhargava’s devoir was to cultivate the staff by spoiling them with Red Cross goodies. And all kept their lips sealed to keep the ‘mission’ under wraps.

Besides, when the nod of assent was given, everybody knew how fraught it was, and the repercussions. They abided unflinchingly. Sample this: As per the script, Chati was to take advantage of the predawn loo-break to slip into D S Jafa’s cell so as to face the blowback together. Second thoughts constrained Jafa to implore Chati to return to his cell in order to simulate normality and provide the three maximum time to make good the escape. Jafa was doubly conscious of jeopardising Chati thus, but Chati willingly embraced that risk. Nothing can beat this as the epitome of teamwork and camaraderie.

Last but not least: The perfunctory “Well done, champ!” abounded and resounded but the three escapees were never feted for their awesome attempt 41 years ago (Vir Chakra was conferred on Grewal but that was for his gallant action prior to the ill-starred sortie). The threesome truly deserves official recognition. Why not honour them at least now through retroactive decoration?

The threesome: Harish Sinhji retired as group captain in 1993, dwelled in Bangalore, tried his hand at carpentry and turned his hand to painting. He succumbed to multi-organ failure in October 1999 (RIP). MS Grewal called it quits as wing commander and plunged into farming in the Terai. DK Parulkar, my battalion commander when I was a cadet at the National Defence Academy, hung up the group captain-uniform in 1987, settled down in Pune, and has since been a man of many parts, juggling the diverse topees of builder, promoter, proprietor and planter.

No comments:

Post a Comment