The Lexington Minuteman Statue (Author's Photo)

19 April was the 240thanniversary of the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. On that day in 1775, a British composite force of roughly 700 regulars and marines was dispatched from their Boston garrison to raid the Massachusetts colonial militia’s stockpiled arms and materiel in Concord. The resultant clashes that morning at Lexington Green and North Bridge were but minor skirmishes compared to the series of engagements that occurred during the raiding force’s afternoon withdrawal to Boston. The British raiders would have been annihilated had it not been for their timely reinforcement with a brigade of regulars on the return trip; the latter alone suffered an astounding 20% casualty rate during its several hours in the field. Whereas only 77 militiamen had met the British at sunrise, nearly 4,000 militiamen and elite minutemen from Boston’s environs had either clashed with or were maneuvering against the Crown’s troops by sunset.

Just 24 hours later, Boston was surrounded by nearly 20,000 militiamen.[1]Many of these men would go on to form the nucleus of the initial Continental Army raised by the Second Continental Congress and commanded by George Washington.

While militarily insignificant in comparison to the afternoon’s running battle, the Lexington salvo and its sequel at North Bridge could not have been more politically and morally decisive. In both cases, British professional soldiers fired first at Massachusetts citizen-soldiers even though the latter’s organized ranks had not aimed weapons at the former’s. The British thereby set the war-opening escalation precedents, with concomitant effects on public opinion in the colonies as well as in Britain (albeit aided by the American Whigs’ vastly superior strategic communications efforts).[2]The American Whigs’ passions for and commitment to their cause were galvanized accordingly; the same cannot be said of British popular (or Parliamentary) sentiments.

It’s a given that an armed conflict of some scale between the Massachusetts Whigs and the Crown’s troops was nearly unavoidable. The political objectives of the British government and the Whig-dominated Massachusetts Provincial Congress were fundamentally at odds, and the latter’s de facto political control over the Massachusetts countryside represented a direct threat to British sovereignty over the colony. Nor could the British tolerate the Whigs’ organization of the colony’s militia units into a well-armed, highly trained, and quickly-mobilizable army controlled by and accountable to the Provincial Congress.

But as we will see, it is not a given that the events of 19 April would unfold as they did. Had the opening volley occurred under different tactical circumstances that day, who’s to say that the Whigs would have captured the political and moral high ground at all? In fact, it is theoretically possible that a different set of British tactical decisions on Lexington Green could have avoided a clash there altogether. Or perhaps with greater British restraint upon entering the town’s center, the way the encounter unfolded might not have been as favorable to the Whig cause.

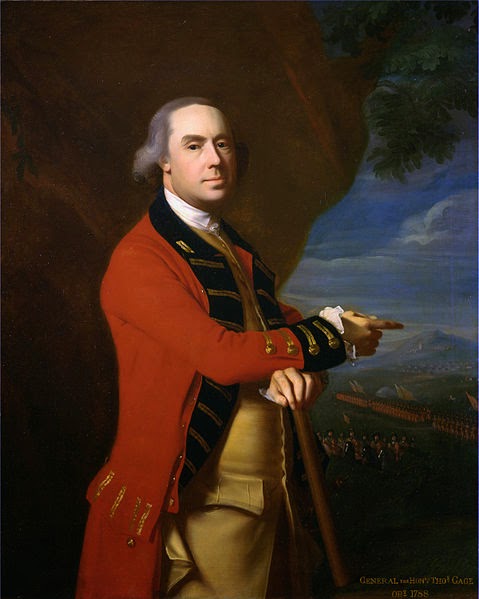

General Thomas Gage

It’s important to note that General Thomas Gage, governor of the Massachusetts colony and commander of the British forces based in the city, fully accepted the possibility of a violent encounter. Gage had received orders from London on 14 April to preemptively decapitate the growing rebellion. The general no doubt reasoned that the most effective means of accomplishing this task was to eliminate the militia’s depot in Concord, as the other major depot in Worcester was out of range for a quick strike. Since every British expedition outside the Boston the previous fall and winter had been met by militia units from the surrounding towns, Gage had every reason to expect the same would occur during the Concord operation. His thinking was almost certainly colored by the failed British attempt to seize cannon in Salem two months earlier; that ‘surprise’ raid had only narrowly escaped coming to blows with the local militia.

It is not shocking, then, that Gage’s first draft of orders for the Concord operation specified that “if any body [‘of men’ inserted above the line] dares [‘attack’ written, then crossed out] oppose you with arms, you will warn them to disperse [‘and’ written, then crossed out] or attack them.”[3]The actual written orders issued to the raid commander, Colonel Francis Smith, did not contain any explicit direction as to what should be done under such circumstances. I agree with historian John Galvin that Gage’s guidance to Smith regarding rules of engagement was likely verbal as to avoid creating a paper trail for an operation Gage had every reason to believe would result in bloodshed.

Colonel Francis Smith

Gage likely assumed that Smith’s force’s size and training would allow it to dominate the handfuls of militia units that he believed would be able to respond in the worst case. His plan was further predicated on operational surprise reducing the speed and mass of the militia’s reaction. Gage simply did not appreciate how the militia’s century-old networks for communicating warning across the colony, doctrine and posture supporting rapid mobilization, and practice in conducting decentralized operations in accordance with a higher-echelon commander’s intent completely undermined his raid plan.[4]

As we well know, superior Whig intelligence collection efforts enabled Paul Revere’s and William Dawes’s triggering of the militia’s warning network on the night of 18-19 April. Between that warning and the delays Smith suffered while ferrying his force across the Charles River to Cambridge, the Lexington militia company under Captain John Parker was fully ready on the town’s Green as Smith approached along the road to Concord that morning. Parker had not received rules of engagement from his regimental commander specific to this particular British expedition, and there’s no evidence that Parker’s orders to his men departed from the Massachusetts militia’s de facto practice of authorizing the use of force only in self-defense or to counter direct attacks against their towns. When his scouts reported the British were minutes away, Parker lined his company up on the Green perpendicular to the road from Boston roughly 100 yards from where the road forked at the triangular Green’s apex. This standoff distance was at the fringe of effective musket range against an opposing formation. He did not place his men in a battle-ready formation. All evidence points to Parker seeking to demonstrate his company’s resolve to the British and thereby deter aggression against the town.[5]

Major John Pitcairn

Smith’s leading elements of regulars under his deputy commander, Royal Marine Major John Pitcairn, approached Lexington Green with muskets loaded and primed. Several factors led to this weapons posture. For one thing, Smith’s force had not progressed very far from its landing area in Cambridge before it became apparent that militia throughout the region were mobilizing and that any chance at operational surprise had been lost. Smith’s scouts, including a party that had briefly captured Paul Revere earlier that morning, had also collected ‘rumor intelligence’ of up to 600 militiamen waiting for the British in Lexington. Just outside the town, Pitcairn’s own scouts reported a lone figure had attempted to fire at them but failed when his musket misfired.[6]Pitcairn and Smith consequently had every reason to believe that they might be entering a hostile situation. Their decision to move to a high weapons posture, then, was logical from a self-defense standpoint.

But inherent self-defense was not their only possible motivation. Gage’s first draft of his operation order suggests that he defined ‘opposition’ by an armed militia unit to mean such a unit’s presence within immediate tactical reach of Smith’s force, that this presence alone would satisfy demonstration of hostile intent (from our modern rules of engagement standpoint), and that Smith was therefore authorized to decide for himself whether or not to warn a militia unit prior to employing lethal force. Given that the entire strategic purpose of the operation was to decisively ‘break’ the rebellion, it is logical to assume Gage verbally empowered Smith (and Pitcairn by extension) to order a precedent-setting first volley for purposes other than the column’s inherent self-defense. It seems to have never occurred to them that the particular circumstances in play on the occasion of setting such a precedent might matter far more than the demonstration of power and resolve they might mean to convey.

Even so, a deliberate move to set a conflict-opening precedent would require that Smith and Pitcairn possess tight tactical control over their force’s firing discipline. Pitcairn claimed in his post-battle deposition that his final order to the British infantry companies on Lexington Green in the moments before the fateful first shot was the equivalent of what today we would call “Weapons Tight.”[7]But Pitcairn did not have tight control over those companies thanks to the actions of a single subordinate, Royal Marine Lieutenant Jesse Adair. London loaded the muzzle and primed the pan, so to speak. Gage aimed the weapon; Smith and Pitcairn were merely the executors. Adair is the man who placed his finger on the hair-trigger.

Adair was reportedly a ‘forward-leaning’ (but at 36 years of age, hardly young) junior officer.[8]He did not hold any command or staff responsibilities in Smith’s force; he was an ‘at-large’ officer in the expedition. Earlier in the morning he had served alongside a few of his peers as Pitcairn’s scouts; this was the group that reported the firing attempt by the ‘lone gunman’ outside Lexington. He and five other ‘at-large’ junior officers accompanied the expedition’s leading companies as they entered Lexington center and found Parker’s Lexington militia company positioned on the Green.

Situation on Lexington Green, roughly 0520 on 19 April 1775 (from Fischer, 192)

In their post-battle depositions, Adair’s compatriots claimed that several hundred militiamen were arrayed before them.[9]Their estimates were likely skewed by the fact that the Lexington Meetinghouse at the Green’s apex obscured full view of the field, not to mention the ‘intelligence’ regarding the Lexington militia’s strength they had collected earlier. Adair almost certainly interpreted Parker’s parade-ground formation as a threat to the British column, even as far back from the road as Parker had positioned his men.

If we assume Adair had authority to order the tactical employment of units not under his formal command (a disturbing proposition to say the least), then what were his options? He or one of his colleagues could have ordered the column to halt and then he or a colleague could have personally scouted the Green to assess the situation and perhaps even speak with Parker. He could ordered the column down the left fork in the road towards Concord and then detached several companies into flanking positions along the Green perpendicular to Parker’s formation so that the latter could not pivot and fire into the main column as it marched by. These two options exemplified restraint in a precipice-of-war situation. They would have allowed time and space for more measured decision-making.

Instead, Adair chose to dispatch several companies down the right fork in the road and into the Green to directly parallel the Lexington company at close range. The quick march he ordered past the Meetinghouse’s north side reportedly became a charge; the two companies of light infantry halted 70 yards from Parker’s men. At the same time, the horse-mounted Pitcairn rode around the Meetinghouse’s south side and onto the Green while the rest of the column turned left at the fork and then halted on the Concord road. By all accounts, combination of British regulars’ “huzzah” cries and the bellowed orders from Adair, the other ‘at-large’ junior officers on the Green, and Pitcairn made any British attempt to exercise tight tactical control impossible. At least some British officers, probably from Adair’s group on the battle line, yelled at Parker’s company to disperse. Measuring the situation, Parker ordered his men to do exactly that. Seeing the militiamen begin to withdraw, Pitcairn ordered the regulars on the battle line to “surround and disarm” them—an action that can only be explained by his not appreciating Parker’s attempt at deescalation. [10]The confusion and sense of imminent danger on both sides must have been profound. Little wonder, then, that shots rang out.

Looking east from the left side of the Lexington Militia Company's lines towards the Green's apex. British battle formation was roughly 70 yards forward from this position. (Author's Photo)

The British were convinced the first shot came from one or more militiamen withdrawing through the area behind Buckman Tavern across from the north side of the Green, or perhaps from a rogue sniper in or behind the tavern itself. The militiamen were convinced one or more British officers fired first with pistols.[11]I agree with historian David Hackett Fischer’s conclusion that both sides’ accounts are probably true, and that if there was a singular ‘first shot’ by someone on one side (whether accidental or deliberate) it occurred almost simultaneously with a singular first shot by someone on the other side.

The post-battle depositions on both sides, though, are consistent in asserting that Parker’s men on the Green did not fire first. And yet they were exactly who came under fire from the British companies on the battle line. The only legitimate targets, if any, were not on the Green. By indiscriminately engaging Parker’s men on the Green, the British undercut any claim to inherent self-defense. In doing so, and as pointed out earlier, they also undercut their political and moral position. The fact that Smith’s expedition failed to achieve any of its operational objectives in Concord and was nearly destroyed on the return trip, while very significant at the campaign-level, is strategically secondary.

Amos Doolittle's late 1775 engraving of the Lexington clash

The stupidity of Adair’s decision is magnified if we take the liberty of indulging in some counterfactuals. For instance, if there were in fact one or more Whig-aligned rogue gunmen not under Parker’s command in the vicinity of Buckman Tavern, then he (or they) would have found it harder to take the British under fire had Adair not deployed the two companies into the Green opposite Parker. Perhaps the rogue(s) could have maneuvered into a different position to engage the column on the Concord Road, but that would have only made it more clear that the fire had not come from Parker’s men. Granted, the subsequent chain of events would likely have been chaotic and might still have led to a direct exchange between Parker’s company and the British. Nevertheless, the facts on the ground would have been different—and the Whigs' assertions of the moral superiority of their cause might have been undercut.

It’s also entirely possible that the first shot would have occurred at North Bridge in Concord if it hadn’t in Lexington. Or perhaps the confrontation at North Bridge would not have resulted in an exchange of fire at all had all involved there not been aware of the hostilities a few hours earlier. All the same, it’s quite likely given Gage’s orders and the overall circumstances that some clash would have occurred either later that day or on a subsequent occasion. Such a clash would not necessarily have resulted from a strategically-impactful failure of British tactical decision-making.

It should be clear from this story that former U.S. Marine Corps Commandant Charles Krulak was quite correct with his concept of a “strategic corporal” two decades ago, except in the Lexington case it was a “strategic lieutenant” who ultimately directed the path of history. Any contemporary junior officer and his or her field grade commander could easily find themselves in a similar brink-of-war situation someday. Unlike the British government in April 1775, though, these modern officers’ political masters might actually want to avoid hostilities.

It follows that much should be learned from the many British operational and tactical mistakes that led to the clash on Lexington Green (of which I have only listed a few). In my opinion, the most important of these mistakes was Gage’s and his subordinates’ failure to appreciate that just because their government was willing to start a war to achieve its objectives didn’t mean the way the war started at the operational and tactical levels wasn’t of critical strategic importance. Neither Gage, nor Smith, nor Pitcairn made any discernable effort to think through exactly what ought to be sought or avoided in a first clash with the Whigs. Neither Smith nor Pitcairn made any discernable attempt to issue clear intentions to their subordinates regarding what to do in a confrontation, let alone to maintain tight tactical control over their force when actually in contact. As a result, they essentially tossed a lit matchbox in the form of Adair amidst several leaking barrels of gasoline. We should thank them for that, as while the results were disastrous to the Crown’s interests, they led directly to the birth of our democratic republic and its enshrinement of natural rights in law.

No comments:

Post a Comment